Wabash County’s Efforts to Preserve Local History

By: INPUT

When you think about history, what comes to mind? Perhaps you consider events that have impacted the world as a whole. Maybe you jump to a specific time in the United States’ history.

The lessons taught in school about history often emphasize the impact each event has on the current world we live in. These lessons often apply on a large scale, but recognizing the history of your town, or even the street you live on, is significant to understanding the place you call home.

Across the Northeast Indiana region, small-town historians and community leaders are on a mission to preserve that history for generations to come. Wabash County Historian Ron Woodward explains that understanding the past can better help us understand how we got to where we are today.

“The more understanding that you have of your local community, the more you understand its local needs and our own personal roles in that history,” he says.

Growing up in New Albany, Indiana, Woodward took a special interest in history in the fourth grade and since then, it’s become a fundamental part of his life’s work. He made Wabash his home, having taught and retired from Wabash City Schools.

“I’ve always wanted to study history and teach it,” he says. “The reason I wanted to teach it was because I wanted to know more when a teacher I had couldn’t answer my questions.”

As a teacher himself, Woodward crafted his plans to immerse students in local history through in-depth information, not just general trends. He says the result was a detailed interweaving of the local community and national trends. This paved the way for a deeper understanding of community roots.

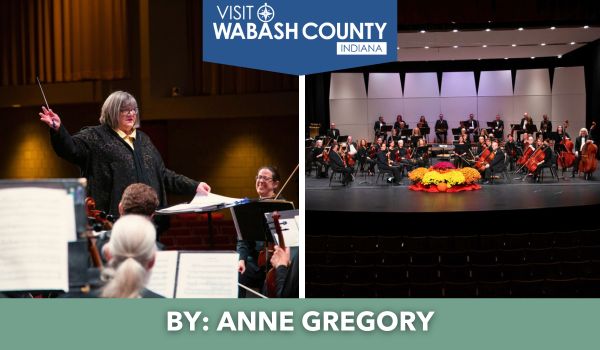

As director of arts for Honeywell Arts & Entertainment and the Dr. James Ford Historic Home in Wabash, small-town history is essential for Carolyn Stoner. After living in Chicago, Milwaukee, and New York City, she says it’s important for residents of small towns to have access to cultural experiences.

“I strongly believe it is just as important for people living in small towns to have access to cultural experiences as it is for people in large cities,” she says. “The history of a small town and the people in it are essential to how our country was built and the lives we live today.”

“Nothing Ever Happens Here”

Woodward says regardless of size, each community holds a rich history that deserves to be told, despite the common troupe– “Nothing ever happens here.”

“When people say, ‘Nothing ever happens here,’ it shows how much we do not know about our own hometown,” he says.

Take Wabash for example. On March 31, 1880, it became the first fully electrically lit city in the world. After which they became a model for other cities that wanted to become electrically lit.

Teresa Galley, executive director of Wabash County Museum says of the event, “It’s definitely our claim to fame.”

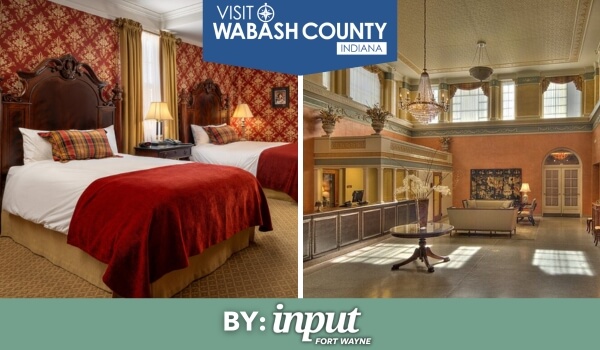

Wabash is also home to the Dr. James Ford Historic Home, a restored 19th-century physician’s home and surgery center, which serve as an example of the evolution of medical practices. As the home’s director, Stoner says the house gives visitors a chance to learn about the Dr. James Ford family and the lifestyle they would have experienced in the years before, during, and just after the Civil War.

Inside the home, visitors can see decor and furnishings from the period, which helps provide insight into what life may have looked like for Wabash residents in the mid-1800s. The home also features flower, vegetable, and medicinal herb gardens, as well as a stone barn, which housed Dr. Ford’s faithful steed, Barney.

Next door to Wabash is North Manchester, a small rural town about an hour south of Fort Wayne that shows even small towns can birth prominent historical people. Laura Rager, director of North Manchester Center for History says that the Thomas R. Marshall Historic Home provides an opportunity to see the home where the former governor and then later vice-president lived as a young child in the 1880s and where he made his rise from a rural home to the White House.

The North Manchester Center for History also features exhibits on the town and other people from its past who have made an impact. Rager says their collection holds nearly 37,000 items.

“The collection contains headstone remnants from Civil War veterans,” she says. “Many are broken and unreadable but one belonged to a member of our local Quaker Community, who assisted with the Underground Railroad.”

Providing a safe place for items that once belonged to or are connected to North Manchester residents is part of what Rager loves about their small town history center.

“I love knowing that we provide a safe place for the last physical connection to these people.”

Whether exploring a one-time historic event, a notable figure in history, or the everyday life of a former resident, learning about the history of the place one calls home provides unique insight into how their community has helped shape the world around them.

Getting Involved To Preserve Local History

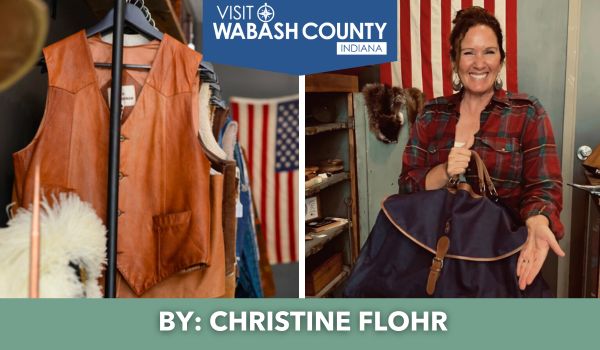

While historians and leaders might be taking the initiative to preserve and share the history of small towns, Woodward explains that community members can also play a significant role in supporting that mission. It can be as easy as reconsidering throwing out old photos or artifacts.

“Too many people throw away family documents,” Woodward says. “Whether taking them to a museum, archives, or libraries, there are people that find this information important to help us understand more about our own community. This will help preserve history.”

Just as he does as a local historian, Woodward recommends setting up a Facebook page to share pictures and information to help preserve pictures and spread information about local history. Sharing photos and information publicly allows communities to interact with the content and share it.

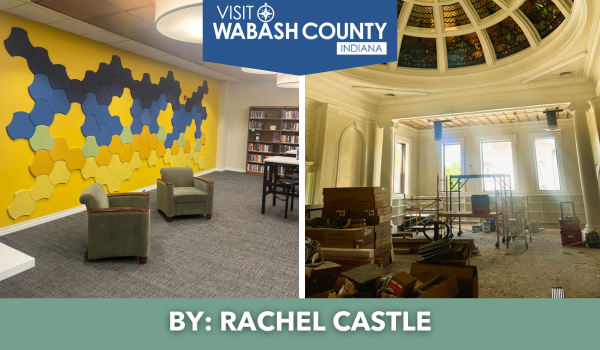

In some communities, residents are taking it upon themselves to preserve local history. In the town of LaFontaine, residents are privately funding a library that houses a genealogy room and a history museum. The LaFontaine Museum Room features the history of Chester Troyer, who founded the library, and information about the town’s history too.

“The people here are truly dedicated to preserving the history of their town,” says Ami Brainard, director of the Troyer Memorial Library.

While not every small town might have a dedicated historical center, Stoner says staying involved in local history can be as simple as asking questions.

“I think the most important thing people can do to preserve our history is to stay curious and ask questions,” she says. “Read the roadside signs and the historical markers. Take that tour of an off-beat, quirky museum. There is so much to gain from learning about the past.”

Supporting the museums that work to preserve the artifacts and details of days gone by is helpful too. Rager says volunteering for local museums can be a fulfilling way to get involved.

“Not only are you sharing your time and talent, but you are also learning about your community and helping to share the stories,” she explains. “I refer to our volunteers as our museum family– you make new friends and strengthen your ties to existing ones.”

She adds that visiting these museums and keeping them afloat is crucial too.

“Keeping local museums alive is the most important thing– visit these museums!” Rager says. “Small museums have many stories to share and are wonderful at connecting us to everyday people.”

Wabash is the focus of our Partner City series underwritten by Visit Wabash County. This series captures the story of talent, creativity, investment, innovation, and emerging assets shaping the future of Wabash County, about an hour Southwest of Fort Wayne.